The 26th June saw the celebration of the feast of Saint Brannock (or Brannoc, or Barnoc) of Braunton in Devon, a sixth-century saint of England’s West Country. Brannock stands as a classic example of the revival of the veneration of the British Saints that lies at the heart of the work of St Seraphim’s. While by no means forgotten in his own locale - about which I will say more in a moment - it was St Seraphim’s that produced the first Orthodox icon and hymn in his honour.

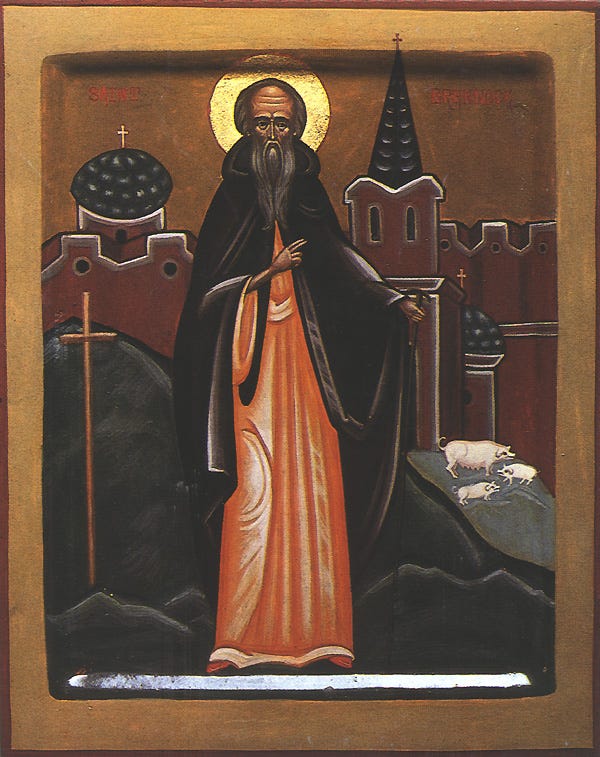

St Brannock of Braunton. Icon by Fr David (Meyrick) of Walsingham

The Troparion, or festal hymn, in his honour, from St Seraphim’s Menaion for June (a collection of hymns for the saints and feast days of a given month) reads as follows:

Righteous tutor of the children of Brychan and great wonderworker, O Father Brannock,/ thou didst win many souls for Christ by thy tireless endeavours./ As Braunton's church may yet hold thy precious relics,/ Pray that we, being ever mindful of our Orthodox heritage,/ may never deviate from the true Faith/ and, thereby, receive the reward of the blest.

One can see in this hymn not only some details of the saint’s life, and the fate of his relics (again, more about which below) but also a particularly clear affirmation that the cultivation of the veneration of the British Saints is one of the best ways in which Orthodox today can foster their sense of rootedness in the long Christian history of these islands and maintain their adherence to the Orthodox faith. The Orthodox faith is not, in other words, an import from the exotic East but something that is enlivened, inspired, and nourished by the rich Christian history of Britain and Ireland.

I have written several times on ‘Orthodox Station’ about taking all this in a non-exclusive sense, i.e. affirming that this rich Christian history is, at least in principle, the common inheritance of all Christians in these lands and beyond, and that the first millennium Church did not suddenly cease being Orthodox and become Roman Catholic at some point in the eleventh century. But the point remains that there is something immensely salutary about getting to know and venerate and love the Saints of Britain and Ireland, entering through them into into the greater chorus of the saints of the whole Church gathered around the heavenly throne - something that has long been at the core of the mission of St Seraphim’s.

I did not know it at the time, but St Brannock established my first connection with the Orthodox station. I was gifted a copy of Fr David’s icon of St Brannock, bought in Walsingham, around about 1989 or 1990. This was in a period of some spiritual wandering and youthful pretension to existential angst on my part. I liked the icon, but didn’t really know what to make of it and had it hanging around on my mantelpiece, much to the surprise of some Orthodox friends whom I encountered later and who happened to come for tea... It was not long after that, in 1992, that I was received into the Orthodox Church.

But enough about me. To get back to St Brannock, he is known only rather dimly through later sources and is often conflated with St Brynach of Pembrokeshire - indeed some sources assume they are the same person. The existence of distinct saints’ days for Brannock and Brynach suggests they are in fact different people but little of this can be established with any great certainty. In any event, and so far as we can glean, Brannock settled at Braunton near Barnstaple in Devon around the middle of the sixth century, an area of sand dunes and salt marsh near the estuary of the River Taw. He went on to found a church and a monastery there. Indeed the place may be named for him: ‘Brannock’s town’ becoming ‘Braunton’ over time. Devon in the sixth century was very much British and Christian, as opposed to pagan and Anglo-Saxon, territory but it was doubtless in sore need of ongoing mission and monastic witness. Brannock initially tried to build his church on top of a hill overlooking the main Celtic settlement. The building work foundered, we are told, due to diabolic interference. In a state of understandable consternation, the saint prayed and eventually dreamt of a white sow and her piglets, being given to understand that where he saw such a group, that would be the place to build the church. The church was duly built down in the valley. You can see the obliging sow and her piglets in the icon.

The present church, which has gone through several iterations, has been dedicated to St Brannock since at least the ninth century. A lively cultus grew up around the saint who has long been associated with miracles of healing and intercession. Such a tradition is arguably more ‘real’ than the inevitable uncertainty surrounding the historical details of the saint’s life. The people of Braunton were able to carry on their veneration of the saint well into the Reformation period, at least into the reign of the first Elizabeth - and that veneration continues today.

A remarkable medieval effigy of the saint survives high up in the Church, partly defaced by Puritan iconoclasts. This image reminds me of the pre-Reformation image of Our Lady of Walsingham that survives, albeit decapitated, in St Peter’s Church in Great Walsingham. The iconoclasts did terrible things but they were not able, by the grace of God, to efface all of England’s rich Christian heritage. Indeed the fact that so much survives, albeit bearing the scars of religious violence, only serves to remind us how precious that inheritance is - a strange combination of resilience and fragility. There also lies nearby, in the grounds of the local Catholic Church, a holy pool named for St Brannock and adorned with an image of Our Lady of Lourdes. There is, in short, much to visit and to see for devotees of Devon’s wonderworker.

Perhaps most significantly, it seems highly possible that St Brannock’s relics have somehow survived the ravages of the Reformation and remain in situ within the parish church, possibly interred below the high altar. Such things are by no means unheard of: witness the modern rediscovery and recent reinternment of the relics of the seventh-century patroness of Folkestone, Saint Eanswythe.

As you might by now expect, St Seraphim’s also produced the first icon of St Eanswythe, an Anglo-Saxon princess who refused marriage and had her father found a monastery on the Kent coast.

Icon of St Eanswythe of Folkestone by Fr David (Meyrick) of Walsingham

She, together with St Brannock, are just two further examples of the clouds of witnesses that surround us so long as we have eyes to see…

More from Orthodox Station next month.

Do you know if a Liturgical service with hymns for matins and vespers has been composed for All Saints of the Celtic Lands?