When we think of the Desert Fathers, our thoughts immediately turn to Egypt, still the imaginative centre of Christian asceticism. Whether we think of early monastic pioneers such as St Anthony, St Macarius, and St Pachomius (all surnamed ‘the Great’) or later figures such as St John Climacus, commemorated on the fourth Sunday of Great Lent in the Orthodox Church, we quite naturally picture the barren terrain of sand and rock in which these figures undertook their ascetic struggles under the cruel and piercing light of the Egyptian sun. And quite right too: this harsh but somehow transparent landscape was indeed an inescapable dimension of their monastic endeavour.

But there are other deserts too, not all of them involving sand. Speaking in terms of spiritual as opposed to physical geography, we can think of the desert of Karoulia at the bottom tip of Mount Athos, or the northern Russian forests so teeming with monks that they were christened a ‘Northern Thebaid’ by analogy with the monastic centre of Upper Egypt. ‘Desert’, etymologically (and this also holds for the Greek erēmos) refers to places that are uninhabited, abandoned, desolate. ‘Wilderness’ is another good term for such places, not least because it carries no promise of sun and sand, but perhaps lacks the obvious connection with ascetic struggle that is conjured up by the notion of the desert in Christian usage, a notion of course connected in the first instance with Jesus’ own archetypal temptation in the Judean desert.

But however we imagine the desert, or the wilderness, we are unlikely to think immediately of England. England, these days, is a rather tame land with scarcely an inch untouched by human hand. As a family, we notice this contrast on long road trips in America, covering distances unimaginable to most British people. We have often driven through vast tracts of land which, even when cultivated, seem ready to leap back into their wild state at a moment’s notice. And of course there are any number of much wilder and more deserted places in the world. England, by contrast, seems rather manicured and heavily populated. This is not to say, I might emphasise, that there is any less sense of the sacredness and sheer pulsating vitality of the creation here – at least if we have eyes to see it – but rather that there is little real wilderness or desert to be had. Thus when we read of the desert of Egypt, or the deserts of Judea, Athos, or Northern Russia, these can seem a little strange or foreign. The exploits of the great monastics of these places can also, by extension, be seen as something out of another time and another place. Not for us, in other words. But England has, or least had, such desert places and even some Desert Fathers (and Mothers). And here we turn to St Guthlac of Crowland and the East Anglian Fens of the seventh century.

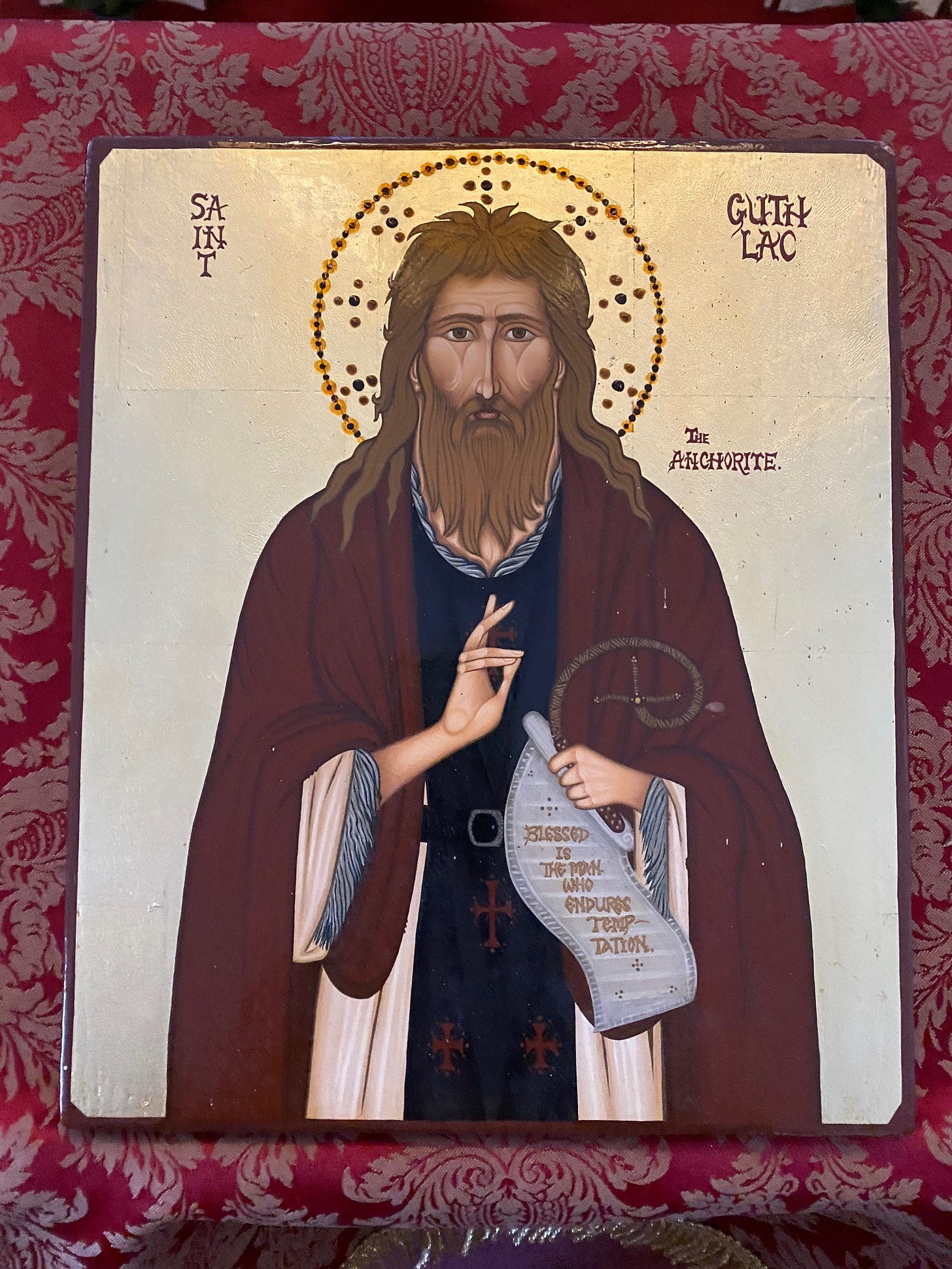

St Guthlac of Crowland. Icon by George Ioannou. Private collection.

The Fens are an area of low-lying farmland comprised of rich black soil that stretches north from Cambridge to the Wash (where King John is reputed to have lost the Crown Jewels). Much of it the result of drainage efforts going back to Roman times but completed in earnest only in modern times. Even today it is a strange place with isolated settlements and, some would say, a tendency to bleakness. But in the Anglo-Saxon period it was an area of boggy marshland dotted with islands such as Ely – even today still known as the Isle of Ely. The eighth-century Life of Saint Guthlac describes the territory like this:

There is in Britain a fen of immense size, which begins from the river Granta [or Cam] not far from the city, which is named Grantchester. There are immense marshes, now a black pool of water, now foul running streams, and also many islands, and reeds, and hillocks, and thickets, and with manifold windings wide and long it continues up to the North Sea.

Charles Kingsley, writing in the nineteenth century, puts it rather poetically in The Hermits:

Of old it was a labyrinth of black wandering streams; broad lagoons; morasses submerged every spring-tide; vast beds of reed and sedge and fern; vast copses of willow, alder, and grey poplar rooted in the floating peat, which was swallowing up slowly, all-devouring, yet all-preserving, the forests of fir and oak, ash and poplar, hazel and yew, which had once grown on that low, rank soil, sinking slowly (so geologists assure us) beneath the sea from age to age. Trees, torn down by flood and storm, floated and lodged in rafts, damming the waters back upon the land. Streams, bewildered in the flats, changed their channels, mingling silt and sand with the peat moss. Nature, left to herself, ran into wild riot and chaos more and more […]

But amidst the bogs there were islands to give shelter to exiles, fugitives, rebels (such Hereward the Wake at the time of the Norman conquest), and those seeking to withdraw as far as possible from human society. Kingsley continues:

For there are islands in the sea which have escaped the destroying deluge of peat-moss,—outcrops of firm and fertile land, which in the early Middle Age were so many natural parks, covered with richest grass and stateliest trees, swarming with deer and roe, goat and boar, as the streams around swarmed with otter and beaver, and with fowl of every feather, and fish of every scale.

It was in the middle of this English desert, and on one such island, that St Guthlac was to settle. Guthlac came from a noble Mercian family with a notably war-like reputation. His birth in the 670s to Penwahl and Tette was, so his Life tells us, marked by heavenly portents but it was to be some few years before this divine favour bore fruit in earnest. In his youth, he emulated his ancestors in military exploits but before too many years were out, he came to realise the fruitlessness of such worldly strife and saw that the truest and most noble of battles lay in the spiritual arena. Taking vows in his early twenties at the double monastery (of men and women) at Repton in Derbyshire he immediately embarked on a life of great austerity, giving up alcohol much to the annoyance (but, eventually, grudging respect) of his brethren. After about two years, having been nourished on the scriptures and the tales of the great ascetics of the Egyptian desert, he sought out the life of a hermit in the wilderness and took himself to the English desert, to the Fens. He heard tell from a certain Tatwine of a particularly remote island known as Crowland that had hitherto resisted all attempts at settlement ‘on account of manifold horrors and fears, and the loneliness of the wide wilderness; so that no man could endure it, but every one on this account had fled from it.’ Here we meet with a parallel, and very likely a deliberate parallel, with St Athanasius of Alexandria’s Life of Anthony. When Anthony went out into the desert, and specifically into an area of pagan tombs, he was not seeking a quiet life but consciously going out to do battle with the demons. So it was with Guthlac, who also settled by an old barrow, or tomb. Called ‘God’s soldier’ in the Life, Guthlac equipped himself for the ensuing struggles by a particularly strict regimen, wearing only skins and taking only a little barley bread and water as his daily sustenance. The struggles, when they came, were fearful indeed and fiendishly many-pronged. Guthlac had to deal with periods of parachoresis or divine abandonment. Perhaps most insidiously, he was once tempted by two demons who suggested that if only he fasted more, he would be that much more the virtuous. At this point he promptly and very wisely ate a loaf of bread. In this measured asceticism he emulated the wisdom of one of the great Desert Mothers of the Egyptian desert, Amma Syncletica, who declared:

There is an asceticism which is determined by the enemy and his disciples practice it. So how are we to distinguish between the divine and royal asceticism and the demonic tyranny? Clearly through its quality of balance. Always use a single rule of fasting. Do not fast four or five days and break it the following day with any amount of food. In truth, lack of proportion always corrupts.

I often think this is one of the sagest pieces of advice to be found in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers.

Guthlac also, again like Anthony, had demons appear to him in all sorts of strange forms:

They were in countenance horrible, and they had great heads, and a long neck, and lean visage ; they were filthy and squalid in their beards; and they had rough ears, and distorted face, and fierce eyes, and foul mouths; and their teeth were like horses’ tusks ; and their throats were filled with flame, and they were grating in their voice ; they had crooked shanks, and knees big and great behind, and distorted toes, and shrieked hoarsely with their voices and they came with such immoderate noises and immense horror, that it seemed to him that all between heaven and earth resounded with their dreadful cries.

The demons, the Life goes on the tell us sometimes even spoke British, the language of the hated and hereditary enemies of the Anglo-Saxons, and a language Guthlac knew from his warring days. Other times the demons took the form of animals:

First he saw the visage of a lion that threatened him with his bloody tusks; also the likeness of a bull and the visage of a bear, as when they are enraged. Also he perceived the appearance of vipers, and a hog’s grunting, and the howling of wolves, and croaking of ravens, and the various whistles of birds; that they might, with their fantastic appearance, divert the mind of the holy man.

Again, the similarities to the struggles detailed in the Life of Anthony are striking. But like Anthony, and this is the main point, Guthlac emerged victorious, holding fast through all these temptations in all humility aided by the occasional and very welcome intervention of the Apostle Bartholomew, on whose feast day he had first settled in Crowland. Much of the imagery used by the writer of the Life is distinctly martial: Guthlac is depicted as equipped ‘with the weapon of Christ’s cross, and with the shield of holy faith’. Such language was doubtless geared to appeal to the warlike instincts of noble and royal Anglo-Saxon households. This kind of phantasmagorical depiction and martial language may not appeal to everyone but is probably best understood as a particularly vivid illustration of the severity of the struggle against the passions and a helpful guide to the kind of strategies one can use to resist such temptations and to channel the powerful inner energies of our being in the right direction.

There is, of course, much more in the Life than the ‘invisible warfare’ of the struggle against the demons. We also find, as we did last time with his near-contemporary St Withburga, a sense of the restoration of the Adamic state by virtue of this conquest of temptation through ascetic effort. In Guthlac it is swallows, rather than does, that betoken this restored relationship between man and the animal kingdom. Guthlac, not unlike Francis after him, seems to have had a particularly special relationship with the birds, putting up with their occasional raiding and feeding them from his own hand. And on one occasion, when he was discoursing with a brother who came to him for counsel:

there came suddenly two swallows flying in and behold, they raised up their song rejoicing; and after that they sat fearlessly upon the shoulders of the holy man Guthlac and then lifted up their song; and afterwards they sat on his bosom and on his arms and his knees.

Guthlac explains to this brother that the animals do indeed become more intimate with those who have lived their lives according to God’s holy writ.

Mention of brethren brings us to another point of contact with Anthony, and indeed many other hermits throughout the ages. The entirely secluded life is rarely, in practice, a permanent arrangement. Disciples tend to gather in great numbers around famous holy men and women. As St Athanasius put it: ‘Anthony left the world, and the world came to Anthony’. Something similar happened to Guthlac: before long a large community grew up around him on Crowland, giving rise to a great Abbey that prospered, as you might guess, right down to the time of Henry VIII. One could mention numerous other parallels here, notably Orthodox Station’s own St Seraphim of Sarov whose extensive periods of seclusion were essentially a preliminary to the intense outward-focused ministry of his later years.

One last detail from the Life. On Holy Wednesday of 714, seeing his end approaching, Guthlac sent word to his sister St Pega to come and prepare his body for burial. The two had not met for some time but Guthlac had evidently not forgotten his pious sister. Pega was also an ascetic of the Fens, a Desert Mother of the English Desert. It was indeed she who oversaw the burial and, a year later, the removal of his incorrupt body to a place of honour within the main church of the nascent monastery. Large parts of the monastery survive to this day, thanks to the fact that the nave remained in use as a parish church. It is well worth a visit.

We did not make it to Crowland itself on the feast day of the saint, the 11th April, but we did sing at St Seraphim’s the Akathist in his honour composed by Fr Philip Steer, whom we have mentioned previously in these pages.

The icon in situ at St Seraphim’s

Here is the opening Kontakion and Ikos of the Akathist to St Guthlac:

Chosen servant of God and flower of the land of Mercia, holy Father Guthlac, we offer to unto thee a meagre song of praise in honour of thine ascetic struggles, whereby thou didst please God, appearing like an angel upon the earth, and, since thous hast great boldness of speech with our Creator, release us from our transgressions by thy prayers that we may cry out to thee:

Rejoice, holy Father Guthlac, great warrior for Christ.

Most noble descendant of famous kings and stern warrior in earthly and heavenly struggles, O holy Father Guthlac, thou wast born amongst the Middle Angles in the days of the illustrious King Aethelred of the English, and thy birth was marked by a heavenly prodigy, for a human hand, shining with red-gold splendour, was seen stretching down from heaven upon the arms of a cross, which stood before the door of the house of thy birth. Therefore, we sing aloud unto to thee and say:

Rejoice, infant destined unto greatness.

Rejoice, mighty son of noble Penwahl, thy father.

Rejoice offspring of modest Tette, thy mother.

Rejoice, favoured by the Lord, Who rules over all things.

Rejoice, man made known before by birth, as a warrior of Christ.

Rejoice, man of great heart, ever mindful of the Lord.

Rejoice, child praised by those who understood the sign at thy birth.

Rejoice, chosen vessel of spiritual gifts to come.

Rejoice holy Father Guthlac, great warrior for Christ.

If you’d like to know more, St Guthlac features prominently in our upcoming British Saints conference: British Saints Conference | St Seraphim's

Accommodation is very nearly sold out but there are still some spots if you live nearby or can source accommodation yourself.

And what of today’s deserts? So far as England is concerned, perhaps the cities are the real spiritual wastelands and the places where the kind of ‘invisible warfare’ practiced by St Guthlac is most needed. We could certainly do with more Desert Fathers like St Guthlac, and more Desert Mothers like St Pega, in our contemporary spiritual wilderness.

Looks like its time for a "English Thebaid" book.

Christ is risen!